Susan Taubes’s Uncanny Chronicles of Home Hell

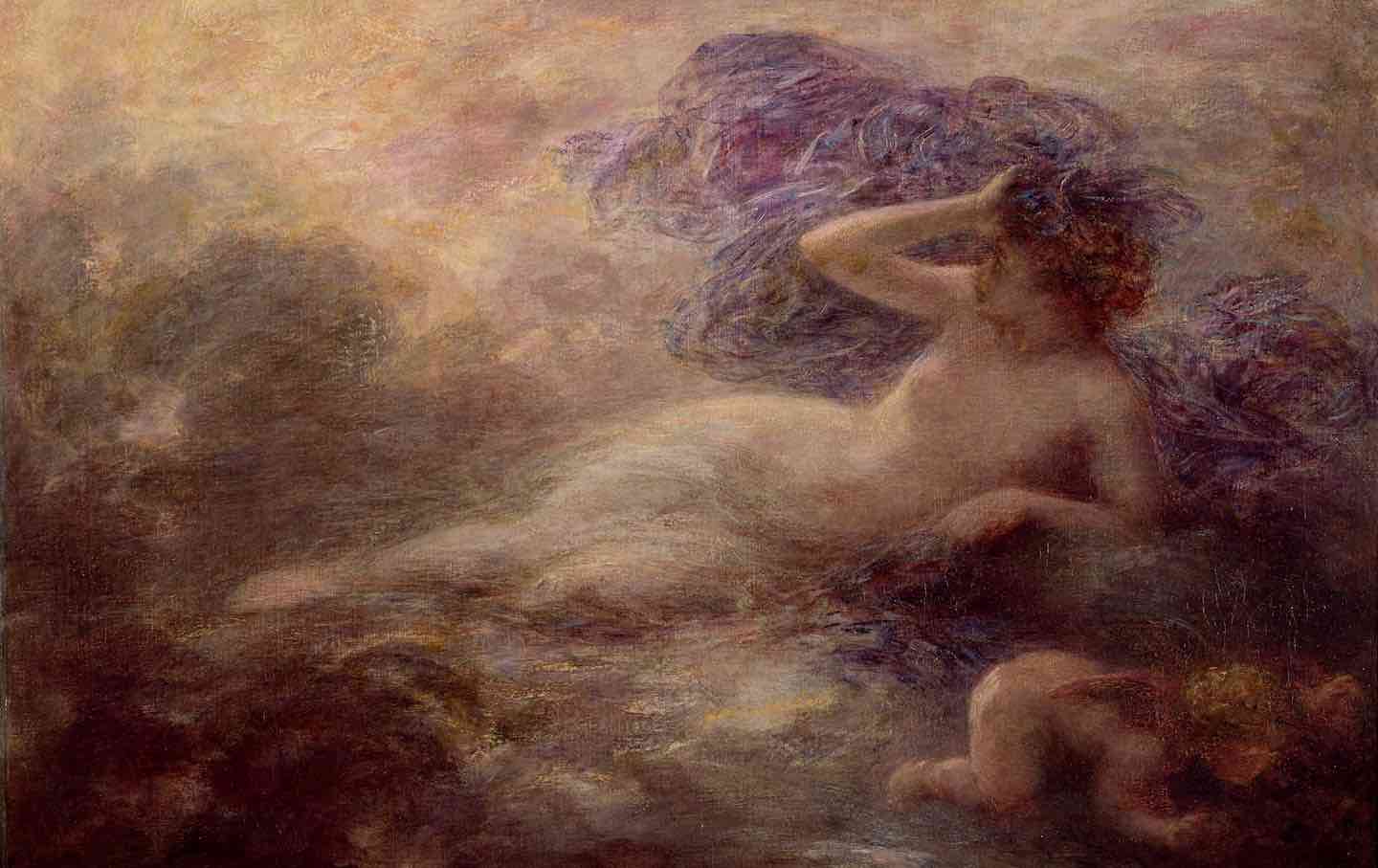

Books & the Arts / January 4, 2024 Her previously unreleased fiction—a novella and brief reviews—in Lament for Julia gaze into the banal and nightmarish travails of married life. The night ( Evening ), Henri Fantin-Latour, 1897. (Photo by Art Photography by the exercise of Getty Photography) Reading Susan Taubes’s fiction would possibly maybe even

Books & the Arts / January 4, 2024

Her previously unreleased fiction—a novella and brief reviews—in Lament for Julia gaze into the banal and nightmarish travails of married life.

The night (Evening), Henri Fantin-Latour, 1897.

(Photo by Art Photography by the exercise of Getty Photography)

Reading Susan Taubes’s fiction would possibly maybe even be uncanny: Mired in the morbid worlds she conjures, a reader is at likelihood of truly feel feverish. Her reviews blur truth and hallucination, reduce by moments of crisp readability. She smothers us via claustrophobic renderings of domesticity: scenes of marriages long gone bitter, affairs that unravel, and the profound loneliness no longer despite however thanks to the presence of but every other.

Books in review

Lament for Julia: And Other Reports

by Susan TaubesBuy this e book

For decades after her death in 1969, Taubes was largely overlooked, hidden in the support of the greater-than-life personalities who surrounded her. It’s telling that in researching this essay, I fell into rabbit holes about other of us: her grandfather, the large rabbi of Budapest; her father, a disciple of Freud who turned a psychoanalyst at the College of Rochester; her husband, a charismatic scholar of religion who was himself the topic of a biography published closing 300 and sixty five days; Susan Sontag, her shut buddy.

Taubes published handiest one fresh in her lifetime. Though panned in The Novel York Times by an ungenerous critic when it came out in 1969, Divorcing was reissued in 2020 to wide acclaim, placing Taubes support on the map of contemporary American letters. Accurate away funny and haunting, Divorcing is painfully attuned to the travails of wifedom and daughterhood. Taubes was lauded for her innovation of the divorce spacewhich replaces the linear march toward union in the marriage space with the ever-splintering paths of a final separation.

Lament for Juliaa collection comprising an eponymous novella and nine brief reviews written between 1961 and ’69, is now published for the vital time. In its pages, readers of Divorcing will think the motifs that preoccupied Taubes in her fresh. She is again chanced on probing females’s attachments to the issues that fracture them, be they men, marriage, or family life. Psychoanalysis is both a lens by which to inquire of this ambivalent relation and but but every other object of ambivalence. But Lament for Julia is no longer merely a prelude to Divorcing; on the opposite, it finds Taubes’s increased mission as author: that she, besides to to being a stoic chronicler of females’s travails in the mid-Twentieth century, is a alive to theorist of ambivalence.

Men emerge as the vital object of ambivalence in Lament for Julia. A majority of these men are fathers who peskily analyze their daughters—that is to state, men without whom our feminine protagonists would no longer exist and but whose presence on the opposite hand vexes them. In “Dr. Rombach’s Daughter,” Marianna, a 13-300 and sixty five days-archaic lady, strives to procure an goal self beyond her father’s diagnoses. Dr. Rombach explains to Marianna in a single scene, “Your coldness and indifference toward me…is exclusively a compensatory mechanism in overcoming your solid oedipal attachment to me.” The same prognosis is proffered in “Swan”: “You are in esteem with me,” Dr. Sigismund, the warden of an asylum, tells his daughter Griselda. “But that you would possibly additionally procure over it.” Marianna and Griselda think solace in writing, which produces a space of personal tale, though no longer essentially reprieve.

Extra on the total, on the opposite hand, the boys who bedevil our feminine protagonists are their husbands and fans. In “The Gold Chain,” Rosalie marries Sylvanus Thrush, a man who’s “very worried and gleaming as a minute one,” with “gentle oldish eyes.” As the story unfolds, he is published to be an effete man, a ghoul who manages to upset both in his frequent absences and his insipid and periodic presence. Rosalie seeks sexual gratification in a discipline out of doors of metropolis with men who’re nameless and cruel. At the story’s conclude, with Taubes’s attribute contact of absurdist magical realism, Sylvanus shrivels to his death as Rosalie presents birth to a baby whose father is unknown. Wandering the streets by myself with her toddler in a basket, she is mocked by the townspeople and in a roundabout way driven wrathful.

“Medea,” a recent rendering of the aged Greek tragedy, follows Isabel Marston, a girl who murdered her two early life after her husband, an art collector, left her for but every other lady. “You don’t mark,” she says to two doctors in some unspecified time in the future of an interrogation.

“Nothing touched him. My life was in his arms. I’m in a position to also no longer even plead, it mattered so minute to him; lower than a form of uncommon objects he’d likelihood everything for, no longer because he wished it to place and relish however fair appropriate for the space of the acquisition and the profit he’d impact in reselling it. He equipped handiest to sell. And I mattered to him even less. He wouldn’t even think what he had done to me. He couldn’t think.”

Isabel’s act of violence and plaintive disclose to be seen throw the dissatisfaction of romantic attachment into sharp relief. Men… can’t live with them, can’t live without them.

“Lament for Julia,” the eponymous novella, is the gathering’s most lengthy therapy of a girl’s ambivalent relationships to the boys in her life. It carefully follows the lifetime of Julia Klopps from childhood into heart age. She is a quite nondescript protagonist in a few ways, born in an unspecified Central European metropolis to a family that is effectively off ample to beget ample cash advantage however no longer fabulously moneyed. Upon first come across, essentially the most striking segment of the novella is no longer Julia herself however the narrator, a form of spirit—a ruin up consciousness born of Julia’s self-alienation, a callous enlighten that personifies the societal norms that press in upon her—that alternately observes, manipulates, and possesses Julia. But as her biography is gradually published, Julia turns into compelling in her anonymity. We are drawn to her precisely because she is an archetype—a girl whose trials evoke hazy, nightmarish recognition. Whereas her mid-Twentieth-century afflictions are no longer quite our beget, echoes of her effort reverberate in the show.

At the age of 15, Julia, then a virgin, begins to indulge in violent sexual fantasies. She is flattered by the admire of a soldier, Bruno, at a Christmas procure together and follows him out of doors for a drink. When he leads her to a hotel, she finds herself unable to leave–no longer because he is forcing her to conclude, however because she feels beholden to her preliminary expression of consent. “For all her innocence Julia knew where it would conclude. Yet how can also she refuse to quench his thirst, critically since it was her irresistible allure that reduced him to this helpless disclose?” The intercourse, when it in a roundabout way transpires, is debasing, and Bruno disappears despite his guarantees to call her in the morning.

A different of years later, Julia in a roundabout way marries Peter Brody, a man who’s largely inoffensive besides the truth that he is meticulously overseen by two overbearing aunts and makes weird sexual requests (“on the total he was speak material to fart in her hand”). The doldrums of family life change into her supreme trial. The all-seeing spirit narrates, “Usually as I watched Julia space the table, I reflected with a obvious awe that on a daily basis for the subsequent twenty or thirty years she would be going via precisely the identical motions, distributing the knives and forks, the wine glasses to the apt and the crystal salad bowls to the left.” Rapidly, Julia spends every evening shedding herself in gin and solitaire.

Stylish

“swipe left beneath to see more authors”Swipe →

When Peter leaves for a piece shuttle, Julia takes on an incredible younger lover, the capricious Paul Holle, who impacts indifference one 2nd and vengeful jealousy the subsequent. Paul reawakens a segment of Julia that had been deadened by marriage: “She wished Paul Holle, all of him always, to place him, to feed him, wash him, flip him inner out, reduce him up, bask in him alive, undergo his early life, fly the excessive seas, live ten lives with him, be everything for him, the relaxation he wished her to be.” But Paul will no longer set her. Peter returns two weeks later, and Paul departs without announcing goodbye.

Relating to the account of Julia’s affair, the spirit muses: “Hang I made too great of it, Julia’s one tall ardour, when it’s fair appropriate but every other banal story?” It’s honest, there would possibly be nothing critically dazzling about a dreary marriage that drives a girl into a torrid affair. However the banality, useless to speak, is the purpose.

The unsparing honesty of Taubes’s fiction invites readers to ask themselves in her pages. Leslie Jamison divulges in her Novel York Evaluate of Books essay on Divorcing that she be taught the radical in the aftermath of her beget divorce. She chanced on herself attempting in the radical “for hope, for diamonds in the ash heap of its effort.”

I myself deliriously scrutinized my beget relationships after downing Taubes’s oeuvre over about a frenzied days: I puzzled if I used to be doomed to place out the archetype as I played support the rhythm of relationships that labored and ones that didn’t. Used to be I simply repeating a sample that has failed me in the past, the one that entraps the females of Taubes’s fiction? Is the comfort equipped by trusty domesticity merely a facade?

But returning to Taubes in a more sober disclose, I spotted that to be taught her for her relatability is practically to leave out the purpose. It neglects the thoroughgoing weirdness of her fiction–a weirdness that resists our makes an strive to map ourselves onto her protagonists.

The cultural theorist Lauren Berlant observes that great of what falls into the bracket of “females’s smartly-liked tradition” (which is to state, everything from so-called “chick lit” to the Cyber web weblog Factual Accomplice Confessions) invokes “the feminine complaint.” “Everyone knows what the feminine complaint is,” they write: “Females live for esteem, and esteem is the reward that keeps on taking.” As Berlant points out, the enlighten with reenacting the feminine complaint is that the reliance on sentimental griping “domesticate[s] fantasies of imprecise belonging as an alleviation of what is anxious to place watch over in the lived valid.” The female complaint provides an outlet for airing frustration, in flip rising an “intimate public” that permits reattachment to an unlivable truth: the suffocating norms of family life, heterosexuality, and domesticity.

At first discover, Taubes’s reviews fragment the markings of the feminine complaint: Admire is poison, romantic family contributors a constant situation of contestation. However the antagonism that roils beneath her fiction thwarts this identification. Even as we fragment her heroines’ woes and are attempting for connection with them, they refuse recognition and fly into phantasmagorical hinterlands. The reader begins to suspect that her beget relation to the protagonists of Taubes’s fiction is, likely, essentially the most ambivalent relation of all.

In a roundabout way, for Taubes, a frictionless relationship can handiest ever be a shaggy dog story. The handiest esteem story in the gathering that would be regarded as inner the neighborhood of “overjoyed” is its shortest piece. Prese rving the span of about a days, “Easter Talk over with” narrates an affair between cousins. The total story is a stack of 1 silly simile atop but every other incredulous scene. Entwined limbs are likened to “the tentacles of an amorous tropical squid.” “Water me!” the narrator’s cousin Hester “gasps” at one point. “Her head rolls up and doing, and I pee in her ear.” But even in this roguish minute piece, a tinge of sadness lingers. Hester wakes up after one passionate night and cries, “I’ve never been so by myself.”

Kathy Chow

Kathy Chow is an assistant editor at The Yale Evaluate and a PhD candidate in spiritual learn at Yale.